Over the course of the last two decades, I have worked from my home base in Nebraska in nearly every state in the country. During this time, I have heard or helped implement rural programs that have had varying levels of interest and success. Here are a couple of programs that I like and how they have been implemented and evolved.

- The 100 Cow Program – Curtis, Nebraska – This program was originally created by the Nebraska Technical College in Curtis. It was a financing program for graduates to buy their first herd of cattle at zero percent financing following the completion of their animal husbandry and other college course requirements. It was effective in helping new ranchers start – but it still tended to preference people from existing ranching families. Extending this program to provide grants (rather than loans) and access to grazing grounds may be helpful. This program has also been used as the backbone of the 100 Tool Program in rural Virginia where many contractors have skills from working in industry but not the technical credentials (i.e. formal training at an academic center) to become licensed. Providing licensure programming along with no interest loans for a pickup and the first 100 tools to a contractor – electrician, plumber, welder, etc. – can be a massive game changer in rural areas.

- Main Street Breweries – Wisconsin is another great example, but these happen all over the country. Basically, towns of 10,000 or less should strongly consider multiple overlapping elements that breweries can create. First, a brewery can be a meeting place for groups from the community. Second, it often becomes a tourist attraction. Third, it exports its product to larger communities in the region. Fourth, it acts to galvanize community gatherings that allow young and old alike to meet and interact. When I provide consulting to regions and cities, I almost always ask about their local breweries. Overwhelmingly, the difference between a vibrant small town and one that has limited main street engagement is the location of a local brewery. This is not the same as a coffee shop or co-working space. Both are viable and good – but breweries add the extra dimension of exporting their product – creating opportunities to bring cash back to the community.

- Main Street Loan and Grant Programs paired with a committed ecosystem builder who has permanent funding. Main streets are not rehabilitated in a day – instead they can take 10 to 20 years to build. However, a successful main street can help revitalize a community and provide quality of life to the surrounding region. Marion, Virginia has done an excellent job of building out a main street that includes numerous local businesses, has become a home for regional artists, and provides quality of life to the region. These programs work by centralizing the effort to apply for national and regional grants to beautify individual businesses. These programs need a long-term cheerleader and executor – thus, the need for an ecosystem builder. Many economic developers do this part-time, but without a full-time commitment to simply building their communities first, attraction efforts are often impractical. Instead, focusing dollars on someone who is actively looking to help local entrepreneurs and small businesses leads to finding money from states, the federal government, and even local philanthropy. Some small college towns typify this type of effort where they have then leveraged college money to build out co-working, coffee shops, and other types of quality of life features.

- Food-to-Table Networks – Rural communities surround bigger communities in much of the Middle. Forward looking states and regions have established clear incentives (financial typically) around buying local product, meat and other proteins, and other locally made goods. These networks then are capable of building up resources through urban customers that create steady demand. In turn, these rural areas are often able to build out more local supply. This has created local networks across the supply chain from wine in Napa Valley to pork to table in Iowa. The starting point is intentionally opening up restaurants, cafeterias, and other buyers to the idea of buying locally from small providers rather than from food distribution companies. Once places start considering this path, regions can facilitate with grants for storage, trucks, and tax rebates (for food and restaurant taxes, for example). These can become powerful multipliers because they build out additional resources – like unique glass bottlers, charcuterie board makers, regulatory and compliance experts, and other niche product makers. Coupling this with better cottage industry and food supplier rules allows for a locally sustainable and dynamic food culture and industry. Portland, Maine is an excellent example of how this has worked.

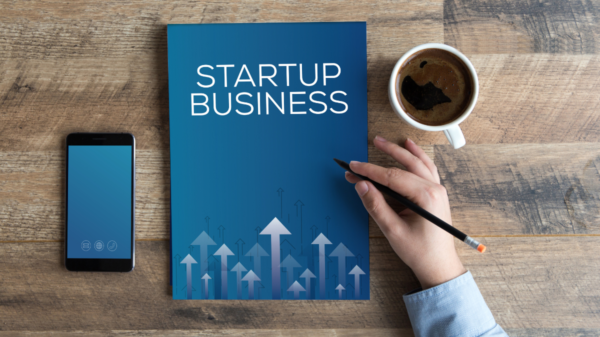

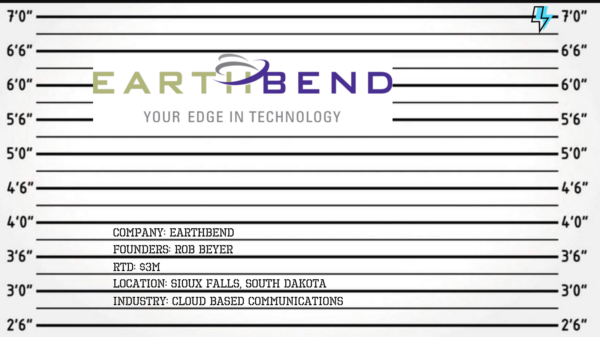

- Most people think of angel or venture capital as requiring a huge investment. However, small angel groups – such as Rain Source from Minnesota/Wisconsin – has been working for generations to make the entry level lower. The organization now has over 40 local funds that support centralized support and due diligence at their headquarters – while allowing for local control in their specific geographies. Thus, Rain runs programs in Appalachia and Minnesota. They have funds of less than $1 million and more than $5 million. This model has scaled effectively and creates an environment where a small locality can provide early equity to companies in the region – allowing for some efforts to build semi-scalable main street businesses (like an exporting food producer that has a location in town) or a truly scalable idea such as e-commerce related products or those that leverage local expertise. Most read the last sentence to mean software – but in rural areas it is often something that is small batch made and exported – such as hunting gear (tree stands) or decorative home goods.

Each of these programs can be tweaked and reworked for a local geography. And each has three common components that are almost always part of the efforts.

Three Common Components for Success

- Leadership training in a community is a critical component. In researching economic development success in rural areas, I often fall back to Ord, Nebraska. Ord is remote and knew that its success would need to come from within. So, it built a leadership program in the late 1990s and 2000s that help galvanize a generation of leaders to build a new Ord – it includes multiple breweries, intentional tourism on the Loup river, and other key elements (a vibrant town square, for example). But, the early leadership training laid the foundation for people that could be entrepreneurs, could understand elements of business building, or just bought in with their own money for buying goods and capital for investment.

- Having a long-term ecosystem builder in place matters. West Point, Virginia is lucky to have Larkin Garbee who has built multiple businesses in town and helped many others. She has helped revitalize main street with an ice cream shop and bakery. She is a prime example of intentional building an ecosystem by building on strengths of a community and not waiting for others to solve the community’s problems. No one is coming to save your town. The towns saviors will be from within.

- Being intentional about having relevant, regular programming is essential. For example, in certain parts of the country – inventors and makers clubs meet at the local library on a certain day every month. In other parts of the country, regional service providers such as the Rural Ideas Network in Dubuque, Iowa help build local programming and deliver it in a location and at scale virtually.

Our last and critical piece of advice is to build what makes sense to you. You can try to do everything that we have listed in this article and it may fail because each does not quite fit your town or region. Focus on what your community’s strengths are and start to gather people that will build along with you. You don’t have to do everything – but you do have to be committed for a while (usually a minimum of five years). It takes a while to galvanize, energize, and go.